ON OLIGARCHIES AND THE IGNOMINY OF TOXIC PETITIONING AT PAN-AFRICAN ORGANISATIONS

By Divine FUH

Africa must find more constructive ways of engaging its problems and those that it considers problematic. But toxic petitioning meant to decapitate young talents is not the way to do it. Promising young leaders need support, especially from elders who themselves know how vicious the work of Pan African leadership can be.

This is a view I nurtured as a teenager while growing up in a small Cameroonian village in which a group of elites stood in the way of progress through regularly petitioning authorities to dismiss, transfer or call back new appointees or rivals, coming from outside their familiar circles, and who they did not consider ‘indigene’ enough to be legitimate. This oligarchy terrorised and held the entire community hostage to the point where almost every development and progressive initiative came to a standstill because everyone was worried about the sabbotage techniques of this visious group; who were involved in and had captured almost every space. My siblings and I, because we play too much, named this group of simply pathetic people we felt sorry for fondly as ‘the petitioners’. In the era of PCs, many of the petitions were typed by one of our Big Brothers in the community who owned a documentation/computer shop – now of late, oftentimes right into the wee hours of the night and early mornings. They petitioners were dedicated, invested, committed, and had transformed it as an art, a professional and a way of life. They were so good at it so much so that at some point in the community, roads, schools, churches, hospitals, government offices, etc had been petitioned such that almost nothing was working; and especially after every appointed qualified and competent person had left for fear of reprisals and sabbotage.

This week I came across another petition written and signed by some of the most respectable elders on the continent in the name of and on behalf of the respectable organizations they head against one of their peers or let’s say one of ‘ours’ at another respectable organization on the continent. The open letter, signed by a record number of over 64 groups and individuals “welcome[d] the withdrawal, by the UN Secretary General, of the appointment of Mr. Matt Hancock, former UK Secretary of State for Health and Social Care and MP for West Suffolk as Special Representative for Financial Innovation and Climate Change of the UN Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA).” This “grave error of judgement by Ms. Vera Songwe [Executive Secretary of the UNECA] and the rescinding of the appointment” was qualified by the signatories, and rightly so, as “disgraceful to and disdainful of all Africans.” This disdainfulness is driven home further, when one considers the large number of elites and trained Africans who qualify for and should have taken up or be offered the position. Even worse is the fact that the former British Health Minister Mr. Matt Hancock spearheaded what some health experts still consider as one of the most disastrous responses to the Covid-19 pandemic, not less that his resignation was enforced by his violation of the same strict prevention regulations that were imposed on the rest of the country.

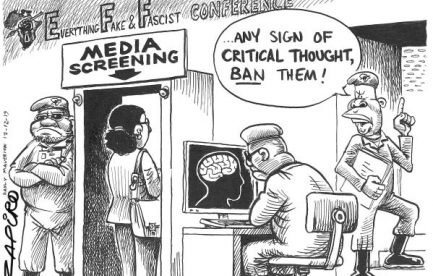

This is not the first time that UNECA Executive Secretary Vera Songwe is mired in controversy as the letter alludes to. In 2019 and 2020, open letters and petitions issues by employees indicted her leadership style and vision, especially what they interpreted as favouratism in hires, mismanagement/corruption in chosing to network with other institutions on the continent, and also what the petition considers to be outright disregard for the African Union and the long historickal relations between UNECA and the African Union. The petition notes that “Unfortunately, it is the latest in a series of acts that show Ms. Songwe’s lack of proper understanding of or regard for the history of the UNECA and a thinly veiled contempt for African institutions.” Furthermore, the signatories point out that “It fits into a history of incidents and acts involving Ms. Songwe which have degraded the UNECA’s role, developed and advanced by previous Executive Secretaries, as an institution serving African interests.” At UNECA, this praxis of checking and balancing the work of managers through petitions appears to be a tradition, as experienced by previous Executive Secretaries.In fact, thinking beyond the UNECA, it is the mode de vie at many, if not all, Pan African and continent level organisations/institutions. Public and livestreamed factional leadership squabbles between delegates at the eminent Pan African parliament that is the epitome of African unity demonstrates just how hard the challenge of privileging African wellbeing is in these spaces where individual career trajectories and ambitions appear to trump everything else. At the African Peer Review Mechanism, it is even more ironic that petitioning and internal squabbles have largely stood in the way of the institution effectively playing its oversight role on the continent. Almost all AU offices are affected/infected.

Recently, similar internal tensions at the African Academy of Sciences has led to the loss of more than half of its staff after key international funders, including the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the UK government and the UK charity Wellcome withdrew from a flagship funding partnership, a situation that according to Nature, did not need to happen and could have been avoided through better stakeholder engagement.

After suspending the AAS director Nelson Torto in 2020 to undertake a forensic audit into allegations that staff salaries and benefits had been inflated without proper procedure, a group of AAS fellows wrote to funders of the AESA initiative and other stakeholders in the funding platform, including the African Union’s development body NEPAD, expressing “deep concern” about the governance of the AAS. In 2020 the re-appointment of Dr. Kinwumi Adesina for a second term as President of the African Development Bank (AfDB) was mired in controversy following governance concerns and allegations of maladministration. Even after having been cleared of any wrongdoing by the bank’s Ethics Committee following a commisioned independent investigation, a petitioning of the process itself raised even further doubts on the institution’s integrity.

At the turn of the millenium Achille Mbembe decided to leave CODESRIA as Executive Secretary to pursue other creative intellectual endeavours resulting to the setting up of WISER at Wits University. During his tenure, the organisation grew its budget and expanded its funding base in the midst of a turmoultous structural adjustment crisis, improved longstanding staffing welfare/benefits, sent off staff to training, enlarged the disciplinary base of the organisation, established international collaborations, modernised the publications programme to internationally disseminate publications, introduced new critical debates and renewed the council’s intellectual agenda. However, his early departure was mired in vicious conspiratorial petitioning by detractors alledging ‘governance concerns’ from an audit by the internationally renowned Ernst & Young firm that Mbembe had newly introduced to undertake credible audits of the organisation’s accounts. Young and also an outsider to the organisation albeit mistakes, his term was disoriented by tensions with the oversight oligarchy. Until date, the campaign to taint Mbembe and further erase that period in the history of the organisation continues. Akin to the current mobilisation against Vera Songwe the vicious public shaming, particularly by elders, activated long lasting rifts in the organisation that almost ruined its future/legacy. Partly instigated by what is known as ‘The Tambacounda emails’, snippets of this toxic castigatin couched as critiques are contained in some of the brilliant responses to Mbembe’s (2004) “African Modes of Self-Writing.”

Ironically, this piece was written in the context of the conservatism that he encountered then in the organisation, and the instrumentalisation of ‘panafricanism’ as a mask for rent-seeking practices and the promotion of the persistent gerontocratic ethos that has captured and held many continental-level institutions hostage. Mbembe’s fight was about how we (Africa) should posit ourselves in relation to the world, in particular how we respond to the unfolding geopolitics of knowledge during that period. Unfortunately, rather than an intellectual dispute, responses to the article also degenerated to vicious accusations of Mbembe being un-African, post-modern, too French, bad administrator/manager, etc.

Ironically, this piece was written in the context of the conservatism that he encountered then in the organisation, and the instrumentalisation of ‘panafricanism’ as a mask for rent-seeking practices and the promotion of the persistent gerontocratic ethos that has captured and held many continental-level institutions hostage. Mbembe’s fight was about how we (Africa) should posit ourselves in relation to the world, in particular how we respond to the unfolding geopolitics of knowledge during that period. Unfortunately, rather than an intellectual dispute, responses to the article also degenerated to vicious accusations of Mbembe being un-African, post-modern, too French, bad administrator/manager, etc.

Vera Songwe

The Tyranny of Elders…

In the case of Mbembe just like with Vera and many of the previous cases I have cited above, the techniques and methodologies of sabbotage are similar, as well as the vocabulary of condemnation. In the attacks against Vera Songwe, the tropes employed are very similar, faulting her for coming from those institutions they loathe (World Bank, Brookings Institute etc), for being too cosmopolitan and obsessed with foreign or neoliberal capital even though themselves mainly dependent on foreign funding.

Spying, reporting on and undercutting colleagues, particularly aspring cadets, especially by oligarchs, is the operating style of these old-fashioned bureacracies. That patronnage, fear of reprisals/counter-reprisals, surveillance/spying, sabbotage/ostracising, petitioning and suspicion, as I observed it, today remain and undermine the intellectual life of CODESRIA is not surprising. During my tenure as Head of Publications and Dissemination, there was a sense that the important mandate and work of the orgnisation was constantly held hostage by a poisonous politics of sabbotage or the fear of it thereof that overshadowed the everyday life of the intellectual agenda.

Petitions are valuable disruptive tools for complaint collectives, and even when not immediately addressed by authorities, initiate a process of reflection. In many instances, and thankfully so, petitions are the only powerful weapons of the weak, especially in institutions where the authority of bureaucratic elites is absolute. As Jabulani Sikhakhane demonstrates, petitioning is “politics from below”, and during the colonial era was used for resistance, complaints, to seek redress, interact with authorities despite distance, and used to inform authorities about the needs of ordinary subjects. In the midst of a patriarchal context, “petition writing granted women agency and opportunities for far greater female assertiveness and civic engagement.”

Yet, petitions, especially when driven by privileged elites, can also serve strategically as a surveillance tool to destroy and undermine the leadership of those persons seen not to be deserving of or insider enough to belong or occupy particular leadership roles/positions. This particular kind of destructive politics of undermining is at the centre of a gerontocratic machine that is in the DNA of many continental institutions/organisations. It is part of a toxic patriarchal and often misogynist politics of Babarisation that treats everyone else as juvenile and incompetent if not authorised; and especially if they have not paid allegiance to or genoflated infrom of Babas. Also because once endorsed by Baba, one is eternally favoured, granted privileged access to mentorship, protected, supported and expected to make gaffes without extraordinarily punitive consequences. After all, as West Africans emphasise “if a child washes his hands, he can now eat with elders/kings”, and “What an old man can see sitting down, a young man cannot see even if standing on top of the tallest tree.” The idea here is for cadets or social subordinates to remain the subject of traditional hierarchies and simultaneously excluded from the lowest levels of the pyramidal hierarchies.

For generations, young men – cadets – have been the beneficiaries of this public stoning and generous violence of pruning by Babas. Scholars observe of the Cameroon Grassfields like in many parts of the African continent, that a practice exists in which those denied toeholds on the ladder of elite hierarchies are ‘infantilised’ and systematically represented as children. Despite having come of age through physical development and other social/political accomplishments, they are treated by elders as toddlers and objects without any valuable life essence, mainly to be seen rather than heard, and only fit to be acted upon rather than acting. Toxic petitioning, particular by privileged gerontocrats and elites against budding cadets whom they should nurture, operates as a cropping mechanism to decapitate. It thus is not surprising that ES Vera Songwe is reproached for aspring to the power circles of the IMF and World Bank albeit controversial institutions, a request that she curbs her enthusiasm and ambition “to cement her links in these power circles.” As a West African proverb points out: “if you rise up too early, the due of life will soak you.”

This trimming praxis is today core to the operational logic of many public institutions, particularly at the continental level, where membership in and loyalty to an oligarchy is absolutely essential for survival. As women occupy these spaces and assert themselves in boardrooms, they increasingly become the target of such violence, open shaming and stalking. This is not just from patriarchs, but also matriarchs who employ the same punitive oligarchical logic to drown aspiring cadets. Scholars of women in leadership positions show from their research that women such as Vera are often perceived to be too emotional to handle such leadership positions, hence the conclusion that they are prone to errors of judgement pointed out in the most recent petition against her.

Amanda Gouws shows how in politics and government, women leaders must cope with stereotypical ideas about themselves as incompetent and ignorant. Even worse, are the very public and visible political incidents – like the current petition against Vera Songwe – frequently deployed to undermine their authority and the entire feminist agenda in these spaces. In her study, Gouws identifies the lack of support to women from the women’s movement as one of the persistent barriers to women’s leadership. In fact, gender norms in many contexts that emphasise the primary role of women as wives, mothers and daughters mean that even when they are amongst the few women in leadership at the continental level, they are systematically bracketed by patriarchy as ignorant and incompetent. In March 2021 the new WTO boss Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, first woman and African to hold the position, former Finance Minister of Nigeria and former Managing Director of the World Bank was described by the headline of three Swiss newspapers as: “This grandmother will become the boss of the WTO”, provoking complaints to the newspapers and an apology from the Media company. With such ideologies, women leaders such Vera have almost no chance to succeed.

But who is Vera Songwe? In April 2017, UN Secretary-General António Guterres appointed Cameroon’s Vera Songwe to succeed Guinea-Bissau’s Carlos Lopes as the ninth Executive Secretary of the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) becoming the first woman to lead the institution in its sixty years history. She took up the position in August 2017. She is well qualified and brought to the position a longstanding track record of policy advice and results oriented implementation in the region, coupled with a demonstrated strong and clear strategic vision for the continent. Before her appointment, she was serving as the former Regional Director Africa for West and Central Africa for the International Finance Corporation (IFC), a position she took up in 2015. She was previously World Bank Country Director for Senegal, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Guinea Bissau and Mauritania (2012 – 2015), Adviser to the Managing Director of the World Bank for Africa, Europe and Central Asia and South Asia Regions (2008-2011) and Lead Country Sector Coordinator (2005-2008). Since 2011, she is a Non-resident Senior Fellow of The Brookings Institute: Global Development and Africa Growth Initiative, and was part of the World Bank Group team that raised an impressive US$49.3 billion dollars in concessional financing for low income countries as part of the International Development Association’s (IDA) 16th replenishment.

Born in Cameroon in 1968 she was educated at the rigorous Our Lady of Lourdes Catholic College in Bamenda, Mankon, before studying at the University of Michigan, USA where she obtained a Bachelors of Arts degree in Economics and Political Science. She then obtained a Master of Arts in Law and Economics and a Diplôme D’Etudes Approfondies in Economic Sciences and Politics from the Université Catholique De Louvain, and then a Ph.D. in Mathematical Economics, from the Center for Operations Research and Econometrics in Belgium. She was recently listed as one of Africa’s 50 most powerful women by Forbes and named as one of the ‘100 Most Influential Africans’ by Jeune Afrique in 2019. In 2017, New African Magazine listed her as one of the ‘100 Most Influential Africans’ and the FT named her one of the ’25 African to watch’ in 2015, the same year in which the African Business Review described her as one of the “Top 10 Female Business Leaders in Africa. This was the same year in which she collaborated with the Tony Elumelu Entrepreneurship Programme that pledged $100 million for African start-up companies. The Institut Choiseul for International Politics and Geoeconomics selected her in 2014 amongst the “African leaders of tomorrow”. In 2013 she was listed by Forbes as one of the “20 Young Power Women in Africa”.

Vera Songwe has written extensively on development and economic issues including debt, infrastructure development, fiscal and governance. She is well published and regularly contributes to development debates across a broad spectrum of platforms across the world including the Financial Times. Her work on policy issues is well acclaimed, and credited for the ratification of the African Continental Free Trade Area Agreement by most countries including Cameroon. At the UNECA her reforms have focused on “ideas for a prosperous Africa”, bringing to the fore critical issues of macroeconomic stability, development finance, private sector growth, poverty, inequality, digital transformation, trade and competitiveness.

Under her leadership, the ECA was the first to call for the Debt Service Suspension Initiative for Africa which made it possible to put over 10 billion dollars immediately in the budgets of African finance ministers during Covid-19. She worked tirelessly on an extension that added another 5 billion dollars to Finance ministers. The ECA was the first institution to call for issuance of Special Drawing rights that delivered over 33.6 billion dollars in new fiscal and reserve resources to African countries. She has worked tirelessly with many others across the continent/globally on the procurement of vaccines for the African continent. These collective efforts resulted to the acquisition of 400 million doses of JnJ, the only sure vaccines we have today on the continent.

The writing of the African Digital Strategy in support of the CFTA by the ECA digital Center of excellence and the AU is a major breakthrough. She’s worked with over 20 countries to support the ratification of the CFTA. Today, the ECA is one of the institutions leading the charge to keep gas as a transition fuel and currently fighting for a price on carbon. She launched a billion dollar clean energy initiative to improve governance of energy sector, crowd in finance and support climate changes; and improved census procedures on the continent to improve Africa’s data capabilities. She designed the training of over 15,000 young girls across the continent in Artificial intelligence, robotics IoT, games and animation; and opened an artificial intelligence centre in the university of Congo Brazza.

Public shaming through toxic petitioning, if not well managed, apart from its intention to absolutely ridicule, crop and destroy particular personalities also has the unintended consequence of damaging institutions badly in need of support, mentorship and good leadership. For years we have clamoured for the introduction of ‘new blood’, women, and disruptors with radically new ideas/approaches into organizations and institutions, many of which have long been hostage to patronage networks and oligarchies. It is our responsibility, especially those of elders and successful elites to support, mentor and seek to guide those emerging role models who must be entrusted with the responsibility to build institutions and train those who must train other people tomorrow. But, as the Nature observes about how to resolve the debacle at the African Academy of Sciences, must stay engaged and seek to build rather than abandon and destroy. As it observes, “Good leadership involves learning from failure and accepting responsibility for mistakes.” The troubling decision to appoint the problematic former UK Secretary of State for Health and Social Care Mr. Matt Hancock as Special Representative for Financial Innovation and Climate Change of the UN Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) has been rescinded. It is time to learn lessons, re-engage and continue the important work of building this continent.

But in order to do that effectively and productively, we must find more constructive ways to engage each other, articulate and deal with our problems and those that we find or define as problematic, even/especially when they are not part of our oligarchies. There is so much work to do, and we have already lost so much time, energy and initiatives to ego wars. So much work, so little time, and the stakes for the continent are so high. Africa, particularly Pan Africanism is everyone’s responsibility and not the monopoly of a few, and everyone/every effort needs to be counted and supported to succeed.

As we inherit and transmit to the next generation we must ensure that some of the destructive and generally misogynist praxes introduced and perfected during the colonial era are swiftly abandoned in favour of more constructive approaches to improving leadership that allow continental institutions to breathe and flourish. Our emancipation requires a new and more caring politics of solidarity. Caring is really hard work, emotional and uncompensated as evidenced in women and feminist struggles. Silencing, shaming and tearing people down publicly are definitely not how to do it. It is impressive to see the number of personalities and heads of institutions that were mandated by their boards to join the petition against UNECA boss Vera Songwe. What is sad is the amount of knowledge and experience accumulated by that group of people through their own work in Pan African organisations/institutions across the continent/globally. In a continent of interdependency and conviviality, no one leads alone. Good leadership is that which considers itself as incomplete. It is never too late for this collective of elders, and all of us in spite of our disagreements, to demonstrate even higher leadership by coalescing and putting their ideas in support of their own. Unless the purpose of the entire exercise is simply malice by an oligarchy aimed at replaying some of the conspiratorial political scripts that this continent must decolonize. Pan Africanism should be an act of generosity, solidarity, caring, handholding and decentering.